Although the emerald zone of Boyacá is still far from becoming a haven of peace and progress, some changes are already beginning to be seen that could imply an improvement in the region.

It is a cold morning in March; the team was waiting for the helicopter that would take it from the Guaymaral Airport to a heliport of an emerald mine in Muzo, Boyaca, it is about 35 minutes of travel and, already in flight, the captain meanders through the few free spaces left by a large wall of dense clouds, this is the full rainy season. In the helicopter travels Charles Burgess, president of the company Mining Texas Colombia (MTC), a subsidiary of a powerful American conglomerate made up of about 30 companies, whose main headquarters are in Houston, Texas, and whose main activities are oil, mining and agribusiness.

Charles Burgess is the main character in this story, as he was the one who in 2009 starred in a commercial agreement between the late “emerald czar” Victor Carranza and a subsidiary of this American company. This contract provided for the modernization of the lines of exploitation of the mines in exchange for a share in the production of the green gem. Years later, in 2013, and harassed by his illness, Carranza sold to this company all the shares of the Puerto Arturo mine, one of the most important in the region. A few months after this millionaire agreement, for which no figures are known, Carranza died.

For many in the region and the country that was a turning point for a region rich in minerals but full of poverty and characterized by an almost total abandonment of the State. In the recently published book The New Green War, Petrit Baquero explains, how despite the generational change in the operation of some mines and the new investments that come from abroad, serious acts of violence persist, although not in the dimensions of other decades. In fact, Baquero’s publication dedicates a whole chapter to the ’emerald gringo’, in clear allusion to Charles Burgess and his active participation in the negotiations with Carranza.

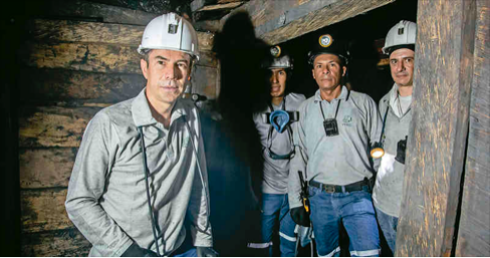

Perhaps for this reason, Burgess only said a couple of comments before and after the short helicopter flight at the end of last March; You can tell that he is not comfortable with media exposure. This secrecy was evidenced once the aircraft stepped onto Boyaca land, as the experienced businessman with extensive experience in diplomatic affairs gave all the spokesman for this report to his vice president, Jaime González. This executive was born in Medellín, but at the age of 4 he emigrated to the United States where he made his life. González, or Jimmy, as he is called by the mine’s henchmen, was a New York policeman for 3 years, then a US diplomat in several Latin American countries, Iraq and Afghanistan. Last year the State Department retired him and now he is Burgess’s right-hand man in Muzo.

How has the mine changed since this change? If some thought that with the arrival of MTC poverty and misery would end, or the royalties from the exploitation of emeralds would increase exponentially, they were wrong, because a company cannot solve all the problems of the community; however, it can be a catalyst for change.

It is necessary for the state to return back to the region, that is, if it ever was. MTC improved the mining exploitation processes and increased social investment in the area of operation with some programs whose impact will be seen in the coming years or even in future generations, but surely these efforts will be insufficient compared to the needs of the population.